MODULE 2B: BASIC ACOUSTICS (continued)

Resonance - Sound Propagation - Musical Instruments

|

Fundamentals of Sound MODULE 2B: BASIC ACOUSTICS (continued) Resonance - Sound Propagation - Musical Instruments |

|

In science, the term resonance describes the phenomenon of maximum energy transfer among two or more oscillating systems, occurring as the vibration frequency of the energy-supplying system (driving system) approaches the natural frequency (resonant frequency) of the receiving system.

Natural frequency: The frequency with which a system would vibrate if energy was supplied to it and then it was left on its own.

Think of pushing a swing, plucking a string, or striking a drum and then letting them vibrate on their own without further intervention.Matching of the driving and natural frequencies maximizes resonance build-up of energy in the receiving system (see this interactive applet - requires the Java plug-in).

Energy build-up from resonance can have extreme outcomes (e.g. Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse; voice breaking glass).When excited/driven, the sound producing parts, or generators, of musical instruments (e.g. strings, drumheads, reeds, metal bars) vibrate at their resonant/natural frequencies.

Resonators of musical instruments (e.g. body and air cavity of a guitar or a violin; air column/cone and material of a clarinet/saxophone/trumpet/organ pipes/vibraphone tubes/etc.) function as amplifiers, enhancing frequencies that match or are close to the range of natural frequency(ies) of a given instrument's generator(s).Natural (resonant) frequencies of physical bodies depend on their physical characteristics such as size, shape, stiffness/tension, material/mass/density, etc.

General guidelines to determine natural frequencies of vibrating bodies:

- the longer a string (e.g. on a guitar) or an air column (e.g. inside a trombone), the lower its natural frequency;

in general, frequency is inversely proportional to length (for wooden/metal bars, frequency is inversely proportional to the square of the length)

- the more massive a string or a drum head, or the larger the air volume inside a space/instrument, the lower its natural frequency;

in general, frequency is inversely proportional to mass

- the higher the tension on a string or a drum head, or the stiffer the vibrating material (e.g. xylophone/vibraphone bars), the higher its natural frequency;

in general, frequency is directly proportional to the square root of tension/stiffness

- the more symmetrical a shape and the less discontinuities, the simpler the resonance (i.e. the less frequency components in the spectrum of the resonance) and the more harmonic its spectrum (i.e. its frequencies are equal or close-to-equal to integer multiples of the lowest natural frequency);

For example

a) a perfect cylinder whose air cavity is excited just by an air stream (flute; pan flutes, etc.) will produce a sound signal with a harmonic spectrum, dominated by its fundamental

b) a struck cymbal will produce a sound signal with an inharmonic spectrum, dominated by higher frequency inharmonic components (overtones).Most musical instruments incorporate resonators with shapes, materials, and construction that result in a range of 'natural' frequencies so that they may respond to multiple frequency components of a single note and to more than one note.

Musical resonators are, therefore, broadly tuned. That is, they are shaped and constructed in ways that support resonance of (or amplification at) a wide/broad range of frequencies rather than a single frequency.

The resonator (e.g. guitar body) starts vibrating because it is in physical contact (e.g. via the bridge) with a vibrating body (e.g. strings), which "forces" the resonator to replicate the oscillations

[ animation example of conductive resonance, showing exaggerated modal vibrations of a guitar body in response to string vibrations ]Sympathetic (free) Resonance

The resonator (e.g. marimba's resonating tubes) starts vibrating in response to wave energy (e.g. from the vibration of struck wooden bars) reaching it via the air

[ video example of sympathetic resonance ]

An intermediate condition between

a) full contact (direct, strong coupling; conductive resonance) and

b) no contact (air coupling; sympathetic resonance)

is weak coupling/conductive resonance (e.g. multiple pendulums with their masses connected by springs).

Weak coupling can promote energy build-up through synchronization among multiple oscillators [ metronome synchronization video example - optional details here ].The figures, below, show the response (y axis) of a resonator with natural frequency f0 when driven at various frequencies (x axis) and at different degrees of damping/friction/resistance/drain [ figure below-right: f0 =440Hz; blue: low damping; green: medium damping; red: high damping ].

Short video on the relationship between driver frequency and resonator response.

Key Observations on Resonator Response

Resonator response:_ is greatest when driven at or near its natural frequency

_ is greater when driven at frequencies that are below versus above natural frequency;for driving frequencies below natural frequency, resonator response matches, at a minimum, the driver's amplitude

resonator response drops quicker as driving frequency extends above versus below natural frequency, dropping to almost zero_ level, sharpness, and "best" resonance frequency decrease as damping increases

In general, the broader the frequency response the lower the maximum response level (why?)

Resonance and Filters

Resonators are analogous to filters.

Both, resonators and filters selectively amplify and/or attenuate different frequencies based on their (physical/electronic/digital) characteristics. The figures, below, illustrate the four most common types of idealized filters.

Q factor (Quality factor or 'sharpness') of a filter/resonator is a measure of its frequency response width.

Q = [Resonant Frequency] / [Response Frequency Bandwidth] [ Frequency Bandwidth: upper freq minus lower freq within a frequency range ]_The heavier the damping, the broader the filter response (i.e. the wider the filter shape) and the lower its Q factor.

_The lighter the damping, the narrower the filter response (i.e. the narrower the filter shape) and the higher its Q factor.

frequency bandwidth where response drops by 3dB

Note: for electronic filters, a 3dB drop corresponds to a

50% drop in intensity (or power) but an ~30% drop in

Voltage [ optional explanation ]_ 10dB Response Bandwidth:< frequency bandwidth where response drops by 10dB

_ >_ Filter slope:

response level change over one octave

[ figure to the right ]Why, do you think, 3dB and 10dB are chosen as markers for a filter's shape?

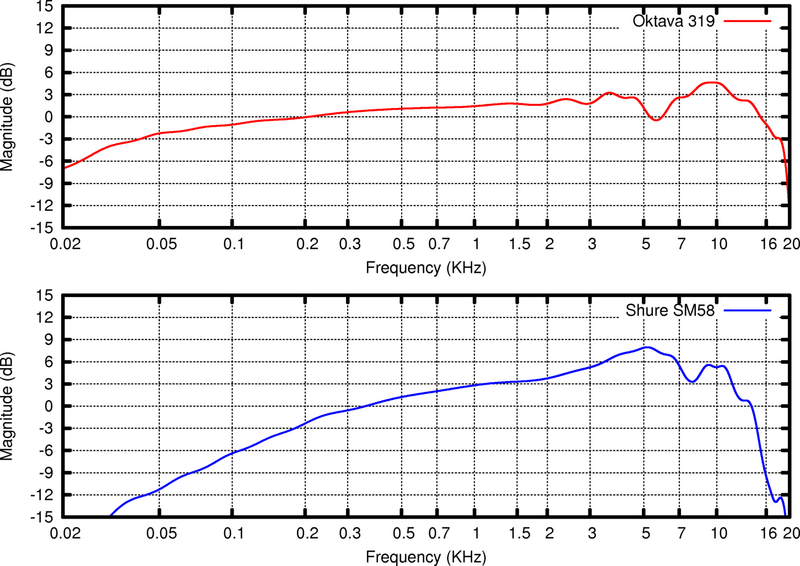

The figures, below, are spectral envelopes, illustrating the frequency response of two popular vocal microphones and are aptly named frequency response curves. They plot level over frequency but only include the spectral envelope line (i.e. the line connecting the tips of each implied, underlying spectral component).Frequency Response Curves show:

- how each microphone resonates (mechanically, via its diaphragm, and electronically, via its circuit) in response to a sound wave and

- how this response varies with frequency.

The frequency response of an ideal microphone would be a flat horizontal line, parallel to the frequency axis, broad enough to extend over the entire frequency range of human hearing (i.e. 20-20,000Hz), and crossing the level axis at (or near) 0. Such response is not practically feasible (why?). The better the microphone, the closer it approximates it.

Microphones closely approximating flat frequency response over the entire frequency range of human hearing:

- faithfully capture the sound waves originating from a source, without altering them by under/over emphasizing any frequencies, a feature that, incidentally, also reduces the likelihood of feedback ringing (why?) and

- support the broadest possible applications (e.g. can faithfully capture sources whose sound spectra occupy the extremes of the frequency range).

How microphones work (animations): outline - dynamic mics - condenser mics

Resonance of Stings, Air Columns, & Plates

Standing waves are a form of resonance and develop at the natural frequency(ies) of oscillating systems.The harmonic spectral components, or harmonics, of the tones produced by standing waves on a string (below) correspond to wavelengths λ that relate directly to the length of the string L.

For each standing-wave pattern or mode of vibration, each loop corresponds to 1/2 wavelength. So, the 1st (fundamental), 2nd, and 3rd modes (and consequently, harmonics) have the following wavelengths λ with respect to string length L:λ1=2/1L; λ2=2/2L; λ3=2/3L. Conversely, L = 1/2λ1 = 2/2λ2 = 3/2λ3.

The two resources, to the right, illustrate the generation of sawtooth standing waves (i.e. modes of vibration) on strings, initiated through conductive (i.e. forced) resonance.

Analogously, the harmonic spectral components, or harmonics, of the tones produced by standing waves / modes of vibration within an air column (below) also correspond to wavelengths λ that relate directly to the length of the air column L. Again, for each standing wave pattern, each loop corresponds to 1/2 wavelength (idealized contexts/shapes).Cylinder open at both ends (below left - flutes, pan flutes, some organ pipes, etc.):

The 1st (fundamental), 2nd, 3rd, and 4th modes/harmonics have the following respective wavelengths: λ1=2L; λ2=1L; λ3=2/3L; λ4=1/2L

Cylinder closed at one end (below middle - clarinet, several non western woodwinds, etc.):

The 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th modes/harmonics have the following respective wavelengths: λ1=4L; λ2=--; λ3=4/3L; λ4=-- (only odd components)

Cone closed at one end (below right - oboe, saxophone, etc.):

The 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th modes/harmonics have the following respective wavelengths: λ1=2L; λ2=1L; λ3=2/3L; λ4=1/2L

The full story is more complicated due to length and tension changes, as a string is excited, and due to "effective" air-column length changes, as a column's diameter and shape change.For most practical purposes, and assuming equal length:

The lowest note produced by strings, conical instruments (e.g. saxophone), and cylindrical instruments open on both ends (e.g. flute) has similar wavelength & frequency across instruments.

The lowest note produced by cylindrical instruments of the same length, but which are closed on one end (e.g. clarinet), has wavelength & frequency corresponding to a note one octave lower.

Resonances of metal plates (e.g. cymbals) produce signals with inharmonic spectra (i.e. with components whose frequencies are not integer multiples of the lowest frequency) and tones with no definite pitch.

The relationship between cymbal dimensions and wavelengths is quite complex but cymbal vibrations do follow specific vibration patterns, also referred to as modes of vibration (see here and below).

Helmholtz Resonators - Bass Reflex LoudspeakersHelmholtz resonators (named after 19th century physicist and physician, Hermann von Helmholtz) are spherical or cylindrical containers with a short, narrow neck, open at one end.

The air in the container acts like a spring and the air in the neck acts like a mass, vibrating because of the 'springiness' of the air inside.where

f: resonance frequency

c: speed of sound

A: neck cross-section area

l: neck length

V: container volume

Consider a 'lump' of air at the neck of the bottle (shaded in the middle diagrams)._ An air jet forces this lump of air a little way down the neck, compressing the air inside.

_ The increased pressure of the compressed air, inside, drives the 'lump' of air back out but, when it gets to its original position, its momentum moves it a small distance outside the neck.

_ This rarifies the air inside the body, which then sucks the 'lump' of air back in, and so on.A jet of air from your lips, for example, is capable of deflecting alternately into the bottle and outside, providing the power that keeps the oscillation going.

The frequency of the vibration is related to the speed of sound in air c, the length l and area A of the container neck, and the volume V of the container, as indicated in the equation, above.

In this "mass-spring"-like system:

_ longer necks ( l ) and larger containers (V) produce lower frequencies

_ wider necks (A) produce higher frequencies.For example, Helmholtz resonance is applied to narrow-band sound absorption (see further below) and to low-frequency amplification via the inclusion of a bass reflex enclosure (or tuned port) to a loudspeaker. Bass reflex enclosures improve a loudspeaker's low frequency efficiency and range of response.

They consist of:

- an appropriately shaped/sized air cavity inside the loudspeaker enclosure, paired with

- an opening/tube connecting the inside of the speaker box with the outside, whose shape and position have been carefully adjusted to support resonances at the desired frequency range.

The air volume of the enclosure acts as the air in the body of a Helmholtz resonator. The supported resonant frequency range is determined by the geometry of the enclosure/tube/opening system, deliberately chosen to smoothly extend the frequency range of the speaker system below its original low cutoff frequency.

In addition, the existence of the port greatly reduces the air pressure variation between the inside and the outside of the speaker box, facilitating transmission of wave energy from the inside of the instrument to the outside (see reflection / transmission, below). More details here.How loudspeakers work (animations): outline - component breakdown - cone & surround

Reflection - Transmission - Diffusion/Reverberation - Absorption

When a sound wave meets a boundary, whether within a medium or separating two media (1 & 2), some of the wave energy may be

_ Reflected (bounce) back, possibly generating standing waves, echoes, or reverberation.

_ Transmitted (pass through or around the boundary).The energy that will pass through/around the boundary may be

_ absorbed (soaked up by the boundary),

_ diffracted (bent around the boundary),

_ refracted (bent inside medium 2), and/or simply

_ transmitted into medium 2.Reflection

Acoustics borrows the basic law of reflection from optics: The angle of reflection will be equal to the angle of incidence, around the reflecting surface's normal*.

[ *normal: in 3D space, the normal to a surface at point P is a vector perpendicular to the tangent plane of the surface at P - in reflection, the incident, normal, and reflected vectors are on the same plane ]

The balance between reflected and transmitted energy at a boundary is determined by the impedance (resistance) relationship of the areas either side of the boundary:

The larger the impedance mismatch and the larger the angle of incidence the greater the reflected energy.

Practically all musical instruments rely on reflection to build up standing waves and produce sound.

They achieve this by involving structures with appropriately placed boundaries and impedance mismatches.If

z1: impedance of the medium from where the sound wave originates

z2: impedance of the medium to which the sound wave movesthen

If z1 = z2 (not displayed): no reflection / total transmission.

If z2 < z1 (below, top-right): reflected & incident waves are in phase.

If z2 > z1 (below, bottom-right): reflected & incident waves are 1800 out of phase.

If z2 <<< z1 (below, top-left) or z2 >>> z1 (below, bottom-left): total reflection / no transmission

OPTIONAL: More specifically:

If I0: Incident Intensity; Ir: Reflected intensity; & It: Transmitted intensity; then

Proportion of Reflected Intensity = Ir / I0 = [(z1 / z2) -1 / (z1 / z2) + 1]2 = [(z2-z1) / (z2+z1)]2

Proportion of Transmitted Intensity = It / I0 = 1 - Ir / II0 = 1 - [(z2-z1) / (z2+z1)]2 = 4z2z1 / (z2+z1)2

[ for a detailed derivation see here - remember that intensity is proportional to the square of pressure ]

Examples of reflection - dependence on impedance

(from the University of Saskatchewan, Department of Engineering Physics)Total reflection at a free end (Z2 = 0)

Z1/Z2 = 2, (i.e. the second medium is lighter)

(reflected plus transmitted energy = original energy)

Total reflection at a fixed end (Z2 = infinity)

Z1/Z2 = 0.5 (i.e. the second medium is heavier)

The reflected wave reverses its phase

(reflected plus transmitted energy = original energy)

Diffusion / Reverberation

Successive, partial, uncorrelated reflections [ i.e. reflections that are not coherent / not in the same or symmetrical direction(s) ] from the surfaces in an enclosure, such as the uneven complex-shaped walls of an auditorium, result in the scattering of the sound waves and diffusion of sonic energy (see below). Repeated, diffused reflections are perceived as reverberation.

Reverberation is a desirable property of auditoriums to the extent that it

a) helps overcome the inverse square law drop-off of sound intensity in the enclosure;

b) reduces overall and frequency-specific level discontinuities within an enclosure; and

c) contributes to the sonic character of a musical style.

Reverberation time is defined as the time it takes for the sound resulting from multiple diffuse reflections to lose 60dB of its original level.Explore qualitatively the top level of these two resources: Reverberation & Reverberation Time (Hyperphysics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State University). You are not expected to follow the links within them or do any calculations. More on reverberation later in the course.

Absorption describes the loss of energy as a wave propagates through a medium and/or strikes a boundary (see to the left). For example, sound can be absorbed through

a) friction as a sound wave propagates in air,

b) trapping as a sound wave strikes a pliable and/or porous boundary,

c) thermal loss of energy, or

d) decoupling and interference when encountering layered boundaries.The degree to which a medium absorbs sound is expressed by its coefficient of absorption, a.

Absorption coefficients range from 0 to 1, are frequency-dependent, and are related to the medium's material and structure._ Brief qualitative outline of absorption and a table of absorption coefficients of common materials.

_ Additional table with absorption coefficients.

- Velocity absorbers (porous materials, such as foam or fiberglass) absorb sound via frictional air movement, are broadly tuned, and work best on mid/high frequencies, which develop high particle motion velocity.

- Pressure absorbers (tuned membranes and "traps," like Helmholtz resonators) absorb sound via interference and diffusion, are narrowly tuned, and work best on low frequencies, which develop high sound pressure levels, particularly near reflective boundaries.

[ optional details on tuned membrane absorbers ]- Hybrid absorbers (modified Helmholtz absorbers and drapes of varied mass/densities/spacing in multilayered arrangements) combine the characteristics of velocity and pressure absorbers to achieve substantial absorption over a broad frequency range. However, they are very costly and require installation space that is usually unavailable or the development of new types of material.

[ optional details: on layered Helmholtz absorbers here & here; on layered drape absorbers here & here ]

|

Diffraction -

Refraction - The Doppler Effect

|

|

|

|

|

Illustrations of diffraction - dependence on

frequency |

|

|

|

|

Play around with this interactive applet exploring the phenomenon of refraction. |

| |

|

|

|

Illustrations of the

Doppler effect - dependence on

source speed |

|

Source velocity = 1/2 * Sound velocity |

Source velocity = 2 * Sound velocity |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

Idiophones produce sound mainly through vibrations of their body - through 3-dimentional standing waves on the entire instrument (cymbals, xylophone, cowbell, etc.) |

|

Membranophones produce sound mainly through vibrations of a stretched membrane - through 2-dimensional standing waves on membranes (all drums, kazoos, etc.) |

|

Chordophones produce sound mainly through vibrations of one or more stretched strings - through 1-dimentional standing waves on strings (guitar, harp, piano, violin, etc.) |

|

Aerophones produce sound mainly through vibrations of air within a volume outlined by the instrument - through 3-dimentional standing waves on bounded air volume(s) (saxophone, oboe, trumpet, organ, etc.) |

|

Electrophones produce sound mainly through vibrations/oscillations of electrical voltage/current (synthesizers, theremin (explanation), etc.) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

Loyola Marymount University - School of Film & Television